Stranger(s) Things: Love, Loss and the Gay Gen Xer in All of Us Strangers

There are movies, there are films, and then there are pieces of cinematic art. Andrew Haigh’s hauntingly beautiful (or beautifully haunting), All of Us Strangers easily falls in the cinematic-art category. (For the purposes of this review/analysis, however, I’ll use the word, film.) Focusing on (queer) loneliness, familial (re)connection and the promise of new love, Strangers is somber and surreal, dreamy and devastating. Andrew Scott inhabits the character of Adam, a screenwriter who spends much of his time alone in his London high-rise apartment building. One night, Harry (Paul Mescal), seemingly the only other resident of the building, appears at Adam’s door, drunk, chatty and certainly flirty. During this brief exchange in the doorframe, Haigh sets up the dichotomy between the two men: outside/inside; younger/older; inebriated/sober; forward/reserved. Cue the phrase: opposites attract. Adam cordially declines Harry’s advances, and shuts the door… for now.

Making Peace with the Past

Later after Adam stares at his blank laptop screen, waiting for the creativity muses to pay him a visit instead, he discovers a photo of his childhood home. He decides to leave the confines of his apartment, and the city, to venture out into the suburbs to revisit his old haunts… and haunt it does. He meets two unlikely inhabitants, to put it simply, ghosts from his past, the meeting serving as inspiration for Adam to invite Harry, his potential future, into his home and into his heart.

As mentioned earlier, Adam’s reserved nature and initial reluctance toward letting Harry in (on varying levels) is representative, perhaps, in part, of his upbringing in the 1980s, at the start of the AIDS epidemic. (The film suggests that Adam was around 11 years old in 1987.) With so much uncertainty and fear surrounding the virus during the decade, these were, perhaps, additional factors that contributed to a future Adam, a gay Gen Xer, to choose abstinence (and self-isolation) over physical intimacy. The younger Harry, likely born in the mid-1990s, is part of the next generation, and seems to have a different, freer approach to sexual experiences. When Adam and Harry begin an intimate relationship, Adam is out of practice, even laughing awkwardly during their first kiss because he has to remind himself to breathe. Later, while Adam is in a bathtub, he is literally and figuratively naked, choosing to share a moment of vulnerability with Harry, who is sitting outside of the tub. Adam admits that for a long time the idea of being with someone physically meant death. These types of honest, heartbreaking disclosures permeate Haigh’s screenplay.

Holding Space

Haigh also chose to shoot parts of the film in his own childhood home. This is a writer and director dedicated to authenticity. One of the many poignant moments finds Adam walking into his childhood bedroom, which has been frozen in time: a boombox sits on his desk; he looks through a few vinyl records that encapsulate English pop music of the mid-‘80s: Erasure’s The Circus (1987) and Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s Welcome to the Pleasuredome (1984). The room looks like a fairly common kid’s bedroom in the ‘80s, but the inclusion of the albums from (and posters of) gay-fronted music groups suggest that a young Adam may have already begun gravitating toward these forms of gay iconography. The room was where 11-year-old Adam could be himself: it was a safe haven from school bullies; his own private quarters for crying; it’s where his musical and artistic interests hopefully brought him moments of joy. Haigh brilliantly incorporates other songs from the decade into the story: Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s “Power of Love” (1984); Alison Moyet’s “Is this Love?” (1986); Pet Shop Boys’ “Always On My Mind” (1987), which you’ll never hear the same way again. The latter, with its theme of regret, expressed from one lover to another, becomes repurposed as an apology from a parent to a child, during the film’s heartwarming Christmas scene.

For All of Us (Strangers)

The story is sure to resonate with many in the queer community, particularly gay Gen Xers, yet the film still allows for something universal, regardless of sexual orientation. Themes of love, loss, and second chances will likely confirm how much we all have in common, particularly after the third and final act, which is emotionally heavy. Ironically, for a story that deals with the importance of closure in order to move forward, its conclusion may, in fact, present more questions than answers, but it almost doesn’t matter with something this beautiful, for All of Us Strangers is a masterpiece that opens the heart, and the mind.

Gotta Have Fate

The Netflix documentary, Wham! is as much about destiny, as it is about one of the biggest pop acts of the 1980s and its global impact over a mere five years. The story of how Georgios “George Michael” Panayiotou and Andrew Ridgeley became the legendary pop group is told mostly through archival footage and audio soundbites.

Meeting at school as pre-teens, Andrew and Yog, Andrew’s nickname for Georgios, became friends with a mutual interest in music. By their late-teens, the pair began writing catchy tunes laced with social commentary, plus ones that embraced the frivolity of youth culture (“Club Tropicana”), as well as others that appeared on their 1983 debut album, Fantastic. “Wham Rap! (Enjoy What You Do),” “Bad Boys” and “Young Guns (Go For It),” positioned Yog, professionally known as George Michael, as the rebellious protagonist, hell- (or heck-) bent on avoiding the 9 to 5 and “death by matrimony,” and set on saving Andrew Ridgeley’s character from a “straight-laced” life (one without George). Besides the (not-so) underlying homoerotic subtext, gay subculture iconography played heavily: leather jackets; tight jeans; aviator glasses—a look that solo George would don again for the Faith era. The musical and visual appeal of Wham! was far-reaching.

Co-crafting the sax-drenched power ballad, “Careless Whisper,” continuing into the Make It Big album (“Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go”; “Everything She Wants”; “Freedom”) and their final, Music from the Edge of Heaven (“Last Christmas”; “I’m Your Man”; “Where Did Your Heart Go?”), both traveled down the same creative pop-music path, only for them to hit the proverbial fork in the road, with personal goals and professional roles shifting as they achieved international success. Watching the documentary through the lens of loss, and letting go in life, adds further emotional resonance to what is essentially a story of unconditional love between friends, with one who must selflessly accept what is, so the other can become who he was destined to be.

Go-go watch it if you haven’t.

This is How You Debut: Revisiting Three Iconic ‘80s Albums

In music, for example, it’s rare that right out of the gate, one gets the top spot or the trophies, but with the right singer, songwriters, production staff and promotional team, for starters, the stars can sometimes align, allowing the debut album to become one of the biggest moments in a career. Just ask these three dance/pop artists: Madonna; Jody Watley; Paula Abdul.

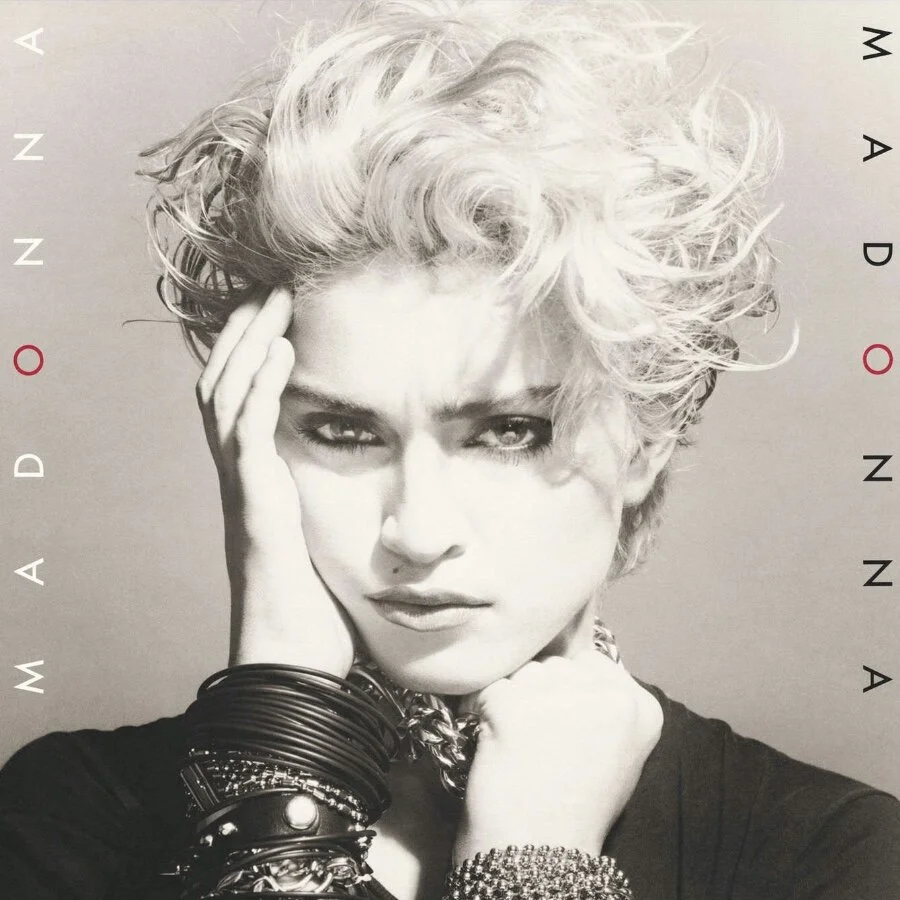

Madonna’s self-titled debut album will celebrate its 38th anniversary in July. (Take a moment to let that sink in.) In looking at the track list, every single single (“Everybody”; “Burning Up”; “Holiday”; “Lucky Star”; “Borderline”) contributed to the solid foundation for what would be a legendary career… who knew? (Madonna, that’s who knew.) The production team on the 8-song 1983 release consisted of Reggie Lucas, Butch Jones, Mark Kamins—the DJ who initially played “Everybody” at New York’s Danceteria—and her then-boyfriend, DJ John “Jellybean” Benitez. Madonna now had the sound, and MTV helped shaped the vision, allowing audiences to meet (eventually) one of the most culturally relevant figures of the 20th century.

Madonna: Sire Records; Warner Bros.

Besides Madonna, another dancer/singer with an incredible debut was Jody Watley. Her 1987 self-titled album featured: “Looking for a New Love”; “Still a Thrill”; “Don’t You Want Me”; “Some Kind of Lover”; “Most of All.” This former member of the group, Shalamar (“The Second Time Around”) hit the MTV rotation as hard as the beats that filled her synth-funk jams. An attitude-rich sound, “Soul Train” dance background and a downtown-fashion street style of thrift-store-inspired petticoats and voluminous skirts, along with equally voluminous hair and signature large-hoop earrings, only added to her vocal and visual appeal. Watley went on to win the Best New Artist GRAMMY in 1988.

Jody Watley: MCA Records

Another dynamic debut: Paula Abdul’s 1988 Forever Your Girl album, which included: “Knocked Out”; “The Way that You Love Me”; “Straight Up”; “Forever Your Girl”; “Cold Hearted”; “Opposites Attract.” (The latter four landed at #1.) Abdul skyrocketed during the music-video ‘80s, when dancers could also shine as singers, as was the case with Madonna and Watley. Abdul first worked behind the scenes, most notably on choreography for Janet Jackson, tour choreography for George Michael, and with many others artists of the era. But when Abdul stepped in front of the camera, she used music video to put tap dance back on trend, even referencing ‘40s Gene Kelly and ‘70s Bob Fosse, in turn, becoming a postmodern Ginger Rogers of the MTV generation.

Paula Abdul: Forever Your Girl: Virgin Records

Three impressive initial offerings, all now-iconic debut albums of the ‘80s.

The Pop Zeal Project (Track 80): U2: “New Years Day”

Cold War

“I will be with you again,” sings Paul “Bono” Hewson on the band’s 1983 hit from the album, War. As Bono began writing the lyrics, they morphed from a love song to his new wife, Alison, into something with a much broader (political) context: the Solidarity movement occurring in Poland at that time. “I, I will begin again.” This backstory is further detailed in Niall Stokes’ book, “U2: The Stories Behind Every U2 Song,” which spans from 1980’s “I Will Follow” to 2009’s “Cedars of Lebanon.”

The video for “New Year’s Day,” directed by fellow Irishman, Meiert Avis, was filmed in Sweden in December 1982, during the dead of winter. According to guitarist, David “The Edge” Evans, the four riders on horseback, implied as the four members of the band, were in fact four Swedish teenage girls in disguise. Also worth noting that in the performance footage filmed in frigid temperatures, Bono is the only member not bundled up, no protective cap and gloves, as he lip-syncs the lyrics while, undoubtedly, feeling the burr.

The Pop Zeal Project (Track 79): Madonna: “Material Girl”

Reference Material

Madonna’s “Material Girl,” from 1984’s Like a Virgin album, is one of the first instances of the singer’s love of playful irony. Vocals that evoke innocence tell the story of a seemingly passive individual who is savvier and more decisive than one would believe. While it appears she is the pursuer of material goods held by “some boys,” by song’s end, she becomes the pursued; there’s a reversal of roles, as heard in the following not-so-veiled verse, full of layered meaning: “Boys may come and boys may go/And that’s all right you see/Experience has made me rich/And now they’re after me.”

Mary Lambert’s video for the song also established just how ironic Madonna felt the song was. Its homage to Howard Hawks’ 1953 Gentlemen Prefer Blondes features Madonna as an actress on a film set, playing the role Marilyn Monroe made famous, a role that had Monroe singing, “Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend.” Yet in this interpretation, both Madonna as the actress and—judging by the “Like a Virgin” lace outfit at the end of the video—Madonna herself believe that daisies can also be a girl’s best friend. Madonna dances a fine line: she pays respect to the film reference, while simultaneously offering critical opposition to “Diamonds” antiquated philosophy.